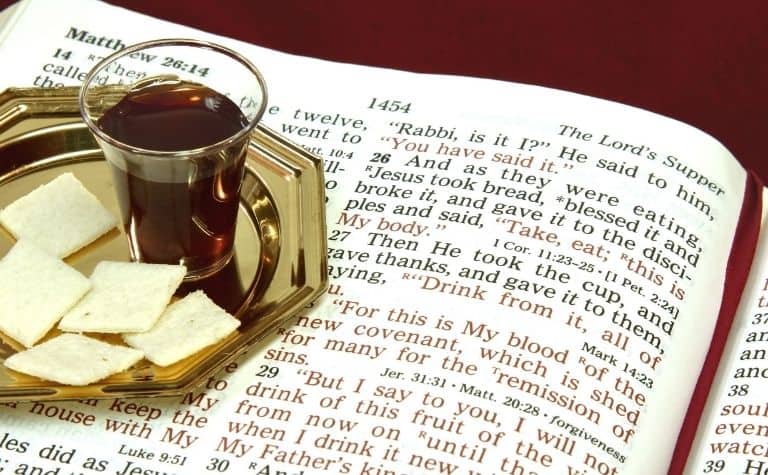

Catholics and Protestants have many similarities regarding doctrine, like the Trinity, and practices, such as studying the Bible. While Catholics, and the vast majority of Protestants, participate in the Lord’s Supper, they disagree on what exactly happens when they consume the bread and cup.

Unlike Catholics, Protestants do not believe in transubstantiation — i.e., the bread becomes the body of Christ, and the wine becomes his blood — because they believe the biblical support for it is lacking. Protestants disagree about the nature of the bread and cup but agree that transubstantiation is not true.

What is transubstantiation? Where does the Bible teach it? What is the Protestant interpretation of those passages? Keep reading to learn answers to these questions and others.

Also, see Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox Similarities and Differences.

What Is the Catholic Doctrine of Transubstantiation?

The Catholic Church teaches that the doctrine of transubstantiation is rooted in the teachings of Christ. However, the church did not fully articulate the doctrine until the 13th century at the Fourth Lateran Council.

Thomas Aquinas later provided a metaphysical explanation for transubstantiation that the Catholic Church still employs today. (Also see Do Protestants Believe in the Saints?)

What is the difference between the “Eucharist” and “transubstantiation”? From the Greek word for “to thank,” the term “Eucharist” is the name of one of the seven sacraments of the Catholic church in which believers consume bread and wine to remember Christ’s death.

The word “transubstantiation” describes what happens to the bread and wine when a participant consumes them.

What is transubstantiation, and what did the Fourth Lateran Council say about it? Transubstantiation is the belief that at the Lord’s Supper, the bread is changed into the flesh of Christ and the wine into his blood. The taste, smell, texture, and appearance of the elements remain the same. The Council explained,

Jesus Christ, whose body and blood are truly contained in the sacrament of the altar under the forms of bread and wine; the bread being changed (transsubstantiatio) by divine power into the body, and the wine into the blood, so that to realize the mystery of unity we may receive of Him what He has received of us.

Did the Church create the doctrine in the 12th century? No. The doctrine of transubstantiation was not created at the Fourth Lateran Council (1215). But up to that point, it was the most complete description of the doctrine. (Also see Here’s Why Protestants Reject the Authority of the Pope?)

The word “transubstantiation” first appeared in the 11th century, yet there is evidence that Christians believed the doctrine, or at least aspects of it, in the first few centuries after Christ. [1]

“Not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Savior, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.” ~ Justin Martyr (100-165)

Where Is Transubstantiation in the Bible?

The Catholic Church teaches that there are allusions to the Eucharist in the Old Testament, such as in the story of Melchizedek, who gave Abram bread and wine (Genesis 14:18).

Passages in the Gospels that describe the Last Supper are also critically important to the doctrine (Mt. 26:17–30; Mk. 14:12–26; Lk. 22:7–39; Jn. 13:1–17:26). (Also see the Catholic’s Lord Prayer vs. Protestant’s Lord Prayer)

However, John 6:22-58, in which Christ teaches that he is the “Bread of Life,” is the foundation for Catholic beliefs about transubstantiation. In the first part of the passage, Christ says, “this is the work of God, that you believe in [Christ] (v. 29)” and that whoever “believes in [Christ] should have eternal life (v. 40).”

In the second part of the passage, Christ talks about eating his flesh and drinking his blood:

- Verse 50: “This is the bread which comes down out of heaven, so that one may eat of it and not die.”

- Verse 51: “I am the living bread that came down out of heaven; if anyone eats of this bread, he will live forever; and the bread also which I will give for the life of the world is My flesh.”

- Verse 52: “Then the Jews began to argue with one another, saying, “How can this man give us His flesh to eat?”

- Verse 53: “So Jesus said to them, “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink His blood, you have no life in yourselves.

- Verse 54: “He who eats My flesh and drinks My blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day.”

- Verse 55“For My flesh is true food, and My blood is true drink.”

- Verse 56: “He who eats My flesh and drinks My blood abides in Me, and I in him.”

- Verse 57: “As the living Father sent Me, and I live because of the Father, so he who eats Me, he also will live because of Me.”

- Verse 58: “This is the bread which came down out of heaven; not as the fathers ate and died; he who eats this bread will live forever.”

Also, see Do Catholics Believe Protestants Go to Heaven?

How Do Protestants Understand Christ as the Bread of Life?

Protestant scholars teach that the key to interpreting the description of eating and drinking in the second part of the passage is Christ’s teaching on faith and belief in the first part of the passage.

For example, the parallelism found in verses 40 and 54 suggests that believing is equivalent to eating, in which case the latter is a metaphor.

| John 6:40 | John 6:54 | |

| English Standard Version | “For it is My Father’s will that everyone who looks to the Son and believes in Him shall have eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day.” | “He who eats My flesh and drinks My blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day. |

| New American Bible | “For this is the will of my Father, that everyone who sees the Son and believes in him may have eternal life, and I shall raise him [on] the last day.” | “Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him on the last day.” |

Some Protestants cite Augustine’s phrase “believe, and you will have eaten” to support their interpretation. [2]

Is the Catholic interpretation a contradiction? The Protestant interpretation of the passage stresses that in the first part of the passage, Christ makes clear that faith alone leads to eternal life.

The Catholic Church, however, uses the second part of the passage to teach that the Eucharist is necessary for salvation, which contradicts Christ’s teaching in the first part of the passage. (Also see Protestant vs Methodist: What’s the Difference?)

Does the Catholic interpretation blur the lines between “flesh” and “body”? Protestant scholars also point out that in the passages about the Last Supper, Christ says about the bread, this is my “body” broken for you (e.g., Mark 14:22-24).

In John 6:49-58, Christ does not use the word “body” but “flesh,” which is a different Greek word. As a result, many Protestant scholars believe John 6 more closely parallels verses like John 1:14 than it does Christ’s description at the Last Supper. “And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14, ESV).

Bible scholar, D.A. Carson, summarizes the Protestant perspective in what is generally considered the best commentary on John available today,

“The language of vv. 53-54 is so completely unqualified that if its primary reference is to the eucharist we must conclude that the one thing necessary to eternal life is participation at the Lord’s Table.”

He continues, “This interpretation of course actually contradicts the earlier parts of the discourse, not least v. 40. The only reasonable alternative is to understand these verses as a repetition of the earlier truth, but now in metaphorical form.”

Please see the related articles below.

References:

[1] Source

[2] Augustine, In Johan, Tract. xxvi. 1.

[3] The Gospel According to John by D.A. Carson. The Pillar New Testament Commentary. 1991. P. 297.

[4] Source

[5] Source

Related Questions

Catholic vs. Protestant vs. Orthodox: What's the Difference?

Roman Catholicism, Protestant Christianity, and the Eastern Orthodox Church are the three historical branches of the Christian religion. Each tradition traces its doctrines and practices to the New...

Protestantism and Anglicanism are branches of the Christian faith that have roots in Europe. Protestantism and Anglicanism have similarities and differences with each other as well as other...